Treatment OverviewThis Domestic Violence Court-Mandated Perpetrator Treatment Program is designed for men and women who have been (or are at risk for becoming) violent with an intimate partner. This program is based on the intervention model described in previous books by Daniel Sonkin.Family safety is the primary concern with every client. The primary treatment goal is the prevention of physical, sexual and psychologically violent behaviors by both addressing the psychological dynamics that give rise to these behaviors and by imparting specific techniques designed to stop aggressive and violent acting out. The attainment of secondary goals, as described in this workshop, are important when addressing the client’s overall mental health functioning. Clinical ModalityThere is currently tremendous controversy in the domestic violence field as to what type of intervention is the most appropriate for this population. The approaches fall into three categories: individual/group psychotherapeutic type, educational profeminist type and family systems type. This program recommends the individual/group psychotherapeutic model for a number of reasons. It is my belief that although education is an important element of all therapeutic encounters, it is not sufficient to address the numerous psychological issues found with person experiencing violence. There is sufficient research in the field of domestic violence to suggest that the vast majority of perpetrators suffer from serious psychiatric disorders ranging from psychoactive substance abuse and affective disorders to disorders of attachment or personality. Therefore, psychotherapy can serve as one effective mode of intervention in addressing the multitude of issues experienced in families where violent is occurring. The vast majority of programs treating domestic violence utilize a group format for a variety of reasons, which will be discussed in detail later in this workshop. The most common reasons for utilizing group interventions are the number of clients referred by the courts, the frequent low motivation levels of the clients and the need for peer support for non-violent approaches to conflict resolution. Typically, group treatment occurs in weekly two-hour sessions consisting of eight to ten men and/or women. Men and women usually attend separate groups, though co-educational programs have been developed and have been found to possess unique advantages over same-sex groups. Under some circumstances, clients are treated individually rather than in group. These reasons will be included in the discussion on suitability and treatment planning. However, the goals and interventions discussed in this program can also apply to individual-oriented interventions. Some clients also receive adjunctive individual treatment as well. Family and Couples TherapyEighteen years ago, when the notion of counseling male batterers was just beginning to become accepted, the idea of counseling couples was not encouraged. In fact couples or family therapy was touted as being ineffective for the purpose of reducing violence, and was thought to promote the belief that women were the cause of men’s violence. Advocates for victims of domestic violence postulated that focusing on the interaction between the man and woman, otherwise known as the systems approach,would give a subtle or not-so-subtle message that the woman was partly responsible for the man's violent behavior. The distrust of the mental health profession toward this systems approach stemmed from the belief that women historically had been blamed for men’s problems as well as for their own and that couples counseling would only reinforce this erroneous belief. What wasn’t considered at the time was that couples counseling could be conducted in such a way as to place responsibility for violence clearly in the hands of the perpetrator. Nevertheless, courageous clinicians and researchers pursued this approach in spite of the vocal disapproval they received from other professionals who bought the party line and from the advocates who initiated this mythology in the first place. Since that time, the research has pointed to the fact that couple or family interventions may be as effective as other forms of treatment, suggesting that there is a place for couples and family therapy either as the primary intervention or as an adjunct to other interventions. There is no one approach to couples counseling — in fact, the term itself is misleading because the different orientations to couples and family therapy vary in their concepts of what causes problems in relationships, and what helps individuals, couples and families change for the better. To complicate matters further many family therapists, like individual theorists, have not only based their approach on research data and theory, but also on what has worked and made sense to them, both professionally and personally. There are many different couples and family intervention theories. For example, object-relations theorists focus on the individuals and what they bring into the marriage. Systems theorists focus on the interaction between the individuals. Narrative or post-modern theorists focus on how the cultural milieu affects family functioning. Individuals who mistake couples or family therapy as focusing only on the system of interaction between couples have erroneously concluded that approaching domestic violence treatment from this orientation blames the woman for the man’s violence. But in fact, one can work with couples and families without giving the message that the victim of violence is responsible for his or her partner’s abuse. Most systems theorists strongly argue that their goal is to empower individuals, not contribute to more blaming — a pattern all too common in intimate relationships. The second argument is that couples or family therapy can become dangerous by inadvertently escalating a conflict that started in the session into a violent confrontation afterward. Of course, this can occur in any modality of therapy. A particularly confrontive or otherwise inappropriate intervention in a group or individual therapy session can trigger a client’s anger and rage, thereby causing the client to become more vulnerable to acting out toward family members. One must approach working with domestic violence with the understanding that there will be re-offenses whether they are directly related to the intervention modality or not. In the final analysis, just as individual therapy may not be appropriate for some clients, so would couples or family therapy be contraindicated for certain clients. Although this workshop is designed for programs offering group intervention, it is important for clinicians to be aware that couples and/or family therapy may be an appropriate adjunctive intervention for a particular client and therefore each case must be evaluated on its own merits. Don't forget, batterer intervention program may not require victim participation in the perpetrator treatment. Nor is couples counseling allowed. In general, couples or family intervention may be utilized as either an adjunct to group or individual therapy or as a primary intervention in lieu of group or individual therapy outside of the court-mandated situation. Generally speaking, couples or family therapy may be utilized in the following situations:

Therapy versus EducationThis workshop assumes that the group facilitators are licensed mental health professionals, or registered trainees or interns under the supervision of a licensed mental health professional. Therefore the model presented here is meant for psychological treatment or psychotherapy rather than for education or self-help. Although this model is considered to be psychotherapy, there is also a strong educational component to the treatment process. This component is necessary due to the fact that many clients being referred by the courts may not initially understand the value of psychotherapy and/or they may not possess sufficient motivation to utilize more traditional psychotherapeutic techniques. Therefore these clients may find a more didactic and practical educational approach less threatening and more appropriate to their stage of change readiness. Another assumption made in this workshop is that groups are open-ended, meaning that new participants are added continuously as space becomes available. However, the assessment and treatment goals and interventions suggested in this workshop are applicable to programs or individuals offering either open-ended or closed-ended groups. A careful reading of the California law suggests that the primary intervention model is education. However, it also states that intervention "...may include, but are not limited to, lectures, classes, group discussions, and counseling." Group PsychotherapyTherapists are encouraged to become familiar with group therapy principles in order to enhance the therapeutic experience of the clients. Irving Yalom, in his book The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, lists a number of important therapeutic factors in group therapy. These include:

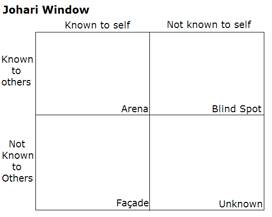

Groups can be viewed as a social microcosm, in that this may be a place where the client’s behaviors, both problematic and positive, are not only displayed but can be understood within the context of the group. The group is an opportunity for clients to learn about themselves and also to learn about others. Group members also play an important role in helping peers view themselves in another way. The Jahari Window (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johari_window) is an example of how this process occurs. In one pane of the window, clients come to understand there are things about themselves that both they and other group members know about (A). In the second pane are the things they know about themselves (B), but others don’t. In the third pane are things about themselves that they are blind to, but others are aware of (C). In the fourth pane are things of which neither the clients nor the others are aware (D). The purpose of the group is to eliminate the unknowns through authentic self-disclosure and to be honest with others about what they are observing and experiencing. Through the group process, clients will ultimately learn new things about themselves and others.

Attending to group cohesiveness is a critical element for therapists to consider when running any type of psychotherapy group. Cohesiveness refers to the group’s sense of we-ness or group-ness. Most experienced clinicians can identify when a group has developed a sense of cohesiveness, but nevertheless it is very difficult to explain why it occurs. According to Yalom, factors that help to contribute to cohesiveness include:

It is important for therapists to understand that while they, and some of the group members, may be overtly attending to the development of a sense of cohesiveness within the group, there are a number of strong forces that may make this development more difficult. First, there is a certain degree of unconscious ambivalence within individual group members, who may be caught between the desire for autonomy and the need for dependence. Secondly, there are varying degrees of difference between the group's need for cohesion, and the needs of its individual members. Lastly, there are unconscious assumptions or dynamics within the group that may quickly become manifest in the process and undermine the group's cohesion. Some groups may operate on the assumption that there is a leader (not necessarily the therapist) who can magically gratify the group's need for security and nurturing. Another dynamic that may evolve is the group members' assumption that they must protect themselves from something threatening --maybe the therapist or even the stated and agreed-upon goals or tasks themselves. Group members may do this by either fighting the threat or running away from it. The most difficult undermining dynamic occurs when there is a pairing-off of some or all of the group members. This problem is usually a direct outcome of encouraging the members of a (domestic violence perpetrator) group to have contact with each other outside of the group. These pairing dynamics may ultimately serve to undermine the group cohesiveness. Some clients may think, either consciously or unconsciously, “Why should I open up or make myself vulnerable in group when I can talk with my peer on the way home?” Pairing off with one another can be one way in which individuals who feel marginalized in society can protect themselves from a vulnerable situation within the group. Group members may be well aware of a particular pairing dynamic. It may or may not be vicariously enjoyed by the rest of the group. In either case, if this dynamic is not discussed openly it will ultimately serve to undermine the group process. These are just a few of the complicated dynamics that rapidly become established within groups. Therefore therapists must not underrate how their inattention to these and other dynamics could potentially sabotage the group’s goals and affect the group member’s lives by compromising their psychological growth. If these or other problematic dynamics develop in a particular group, it is not an indication of failure but rather an indicator that the group process is “cooking.” Herein lies the potential for transformation and genuine growth. However, it takes the acumen of a seasoned clinician to seize this opportunity. In summary, the most helpful factors for clients about the group process include:

Length of TreatmentAccording to the State of California law PC1203.097, persons convicted of acts constituting domestic violence are required to attend a minimum 52-week educational program as a component of their probation. Probation Departments require that clients referred to these programs usually expect that the clients will complete their 52 sessions within a specified time period (such as sixty weeks). This additional time allows for a certain number of missed sessions due to illnesses, holidays, etc. Each jurisdiction has it’s own requirements, therefore therapists must find out the specific expectations of their local probation department. Is there something magical about this number? Not really. In fact, recent research evaluating physical violence re-offenses or re-arrests indicates that programs get diminishing returns after thirty to thirty-six weeks of treatment.The average success rate in treating domestic violence is approximately forty to sixty percent of clients will commit acts of physical abuse within two years post treatment. Some programs that are sixteen weeks in length have demonstrated the similar (40-60% reoffense rates) results when compared to programs more than twice as long. Clearly, there is no evidence that 52 weeks of treatment is necessary to stop physical violence patterns. Most perpetrators learn early in treatment (if they didn’t already know it) that there is huge societal intolerance for domestic violence, that it is against the law, and that similar continued behavior will most probably result in arrest and possible imprisonment. This realization provides incentive to cooperate with the treatment provider’s expectations. However, empirical research also suggests that non-physical violence (e.g. mental degradation, threats, destroying property, etc.) is the most difficult behavior to change, with less than a ten percent desistance rate when evaluated over two years post treatment.From these data, it seems that physical violence is easier to stop than non-physical violence. This in part has to do with the lack of agreement of what behaviors actually constitute non-physical violence. In addition, non-physical violence is much harder to quantify than physical violence. When someone hits it is much easier to identify, measure and quantify than when someone acts in an intimidating way. Most clinicians working with victims or perpetrators are well aware that non-physical abuse is far more pervasive in these relationships than is physical violence. Psychologically abusive behaviors are not always distinct acts, like a slap or a punch. Non-physical abuse is better characterized as a pattern of behavior. These patterns are primarily designed (often unconsciously) to create emotional distance, protect the self from vulnerability, control personal discomfort by controlling others, and regulate dysphoric moods. Although it has not been supported empirically, I believe that non-physical abuse is directly linked to psychopathology and primitive defenses. Therefore, clients may succeed in stopping their physical violence but find less success in learning to change these longstanding primitive coping mechanisms that heavily contribute to non-physical abusive patterns in their intimate relationships. I have found that education, changing attitudes and social consequences go only so far in addressing these deeper psychological issues with violent individuals. The advantage of longer treatment, such as that mandated in California, is that it affords the clinician a greater opportunity to address these more in-depth clinical issues, which could ultimately lead to stopping the non-physical abuse in addition to the physical abuse. I don’t believe the activists who lobbied for this longer intervention had this goal in mind; however if clinicians can capitalize on a longer treatment experience for this generally resistant population, then all the better. Many states have mandated much shorter treatment requirements than has California. Many clients enter treatment assuming that they will only be required to attend for fifty-two weeks. Therefore it is important that persons who evaluate clients for treatment convey to them that, according to law, treatment is a minimum of fifty-two weeks (or the required minimum in your state). Clients should clearly understand from the onset that treatment beyond the required minimum may be recommended if they have not demonstrated attainment of the treatment goals, which includes physical and non-physical abuse. Missed AppointmentsAnother issue relevant to the length of treatment is that of missed group sessions. Many programs have policies about missing groups. For example, in Sonoma County the Probation Department and the local treatment providers have determined that a client may not miss more than six sessions during the fifty-two week program. Clients are allowed four unexcused absences or no-shows. An unexcused absence is when the client calls the program less than one week prior to the appointment, for any reason, indicating that he/she cannot attend (canceled appointment). A no-show is when the client misses a meeting and does not call the program prior to the scheduled appointment. All unexcused absences and no-shows are typically charged at the assessed fee. Clients are also allowed two excused absences. An excused absence is when the client informs the counselor of a vacation or other preplanned event that obligates missed sessions. These excused absences must be cleared with the group leader at least one week in advance of the missed session. There is no charge for excused absences. However, all missed sessions (unexcused, no-shows and excused) must be made up within sixty weeks after the official enrollment date in the program. Make-up sessions are typically charged at the assessed fee. In addition, according to this local policy, clients are not allowed to miss a session during the first six weeks of treatment. Clients who miss during this probationary period are terminated from the program unless the absence occurs as a result of extenuating circumstances (e.g., hospitalization, death of family member, incarceration). Clients who miss more than the six allowed absences may be terminated from the program as well, although in this case too exceptions may be made as a result of extenuating circumstances. In Sonoma County, a good working relationship between providers and the probation department has resulted in mutually satisfying outcomes for logistical issues like missed appointments. When treating a court-mandated population, it is critically important that clinicians set clear expectations in regard to attendance. This is one area where clients are likely to act out their resistance to psychological intervention. As with other defenses, clients can use missed sessions or tardiness as a way to avoid dealing with, or to protect themselves from, feelings about themselves (e.g., a sense of defectiveness or lack of self-esteem) and others (e.g., lack of trust or fear of dependency) -- which must ultimately be addressed within the clinical setting. Setting the frame of treatment doesn’t guarantee these defenses will not be activated, but it does provide the necessary structure to deal with these behaviors and the underlying unexpressed thoughts and feelings that give rise to the acting out in the first place. Dealing with missed appointments clinicallyAs indicated above, many clients act out conscious or unconscious psychological dynamics by missing appointments or arriving late to their sessions. These dynamics may include: their ambivalence about treatment, unexpressed hostility toward the therapist or other group members, anger about being forced into treatment in the first place, fear of facing their psychological pain and vulnerability, inability to acknowledge that they have any problems at all, just to name a few. This acting out must first be addressed clinically with the client. Although it is important that clinicians set firm limits around attendance issues, it is also critically important that the therapist interpret the meaning of the behavior with the client. All too frequently therapists set these limits in a confrontational manner, without helping the client understand the feelings and needs behind his or her behavior. This confrontational style of working with clients may only exacerbate the client’s negative feelings about the therapist or the group experience in general. On the other hand, a clinician may confront and interpret a client’s acting-out only for so long. Eventually, a decision regarding a client's continued participation in the group or program may ultimately need to be made. As difficult as this process can be, it lets the other group members know that the therapist will help them as long as they want to be helped but after some point the agreed-upon rules will be enforced. Other Treatment ModelsBelow are a list of four online papers you must read three of them to complete this course. One of those articles must be the Critique of the Duluth Model. Click on the links to access them. They are all in Adobe Acrobat format, therefore you need to have the free Adobe Reader on your computer. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy with People in Abusive Relationships: Treatment Outcome or Stopping Wife Abuse via Physical Aggression Couples Treatment or Dialectical Behavior Therapy in the Treatment of Abusive Behavior or The Duluth Model: A data - impervious paradigm and a failed strategy

Required Questions:>When you are ready to move on to the next section of this workshop click the link below.I am ready to move on! |